Writing long-hand is an exercise in erasures or cross-outs, depending on whether pen or pencil is your instrument of choice. Long-hand lays waste to a lot of paper. Brilliant words have been irretrievably lost to long-hand; many a writer has erased faulty phrases or wadded up and tossed pages black with cross-outs, only to discover down the line they’ve thrown away something valuable.

On the upside, hand-scrawled words on a page are easier on the eyes than pixels on a screen. When the power goes out, the writing goes on. And since long-hand is quiet, long-handers can keep writing late into night, even if they’re writing in shared spaces.

Still, the real allure of long-hand lies in the magic of pen-to-paper. The near-constant connection between the two creates a palpable flow of words no other method can rival. For the long-hander, the flow of ink and the flow of ideas are inseparable.

Was a time, the word “writer” conjured the image of a geeky author hunched over a typewriter (Mary McCarthy, author of The Group, pictured below). By and large, authors are still geeks, but the technology of writing machines has advanced so far beyond the typewriter, that iconic image is now little more than nostalgia.

As I pointed out in my last blog-post, typing is faster and neater than long-hand and offers equally sensuous pleasures. Indeed, typing on my antique Underwood was a physio-sensory adventure. From attacking the keys, to the “click-clack” musical underscoring, to the rewarding ratchet-and-ding of a manually-operated carriage return, to hand-rolling the paper in and ripping it out, to the quirky landing the “a” keybar made on the page, writing on that old relic was great . . . in a sentimental, living-history kind of way.

The biggest problem with writing on typewriters (aside from the keybars getting stuck) is the one-way traffic. Fixing small typos ain’t so bad. Fixing larger issues is awful. Once a page is done, going back to swap a couple phrases, change a sentence, or move a paragraph means re-typing the whole damn thing.

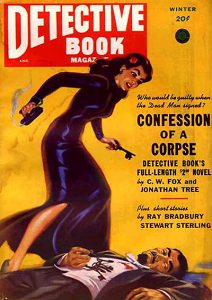

Unless you’re writing pulp. True pulp fiction is written in one straight shot, no corrections till the story is done. When you’re getting paid by-the-word and the pay is pittance, you don’t spend a lot of time re-typing.

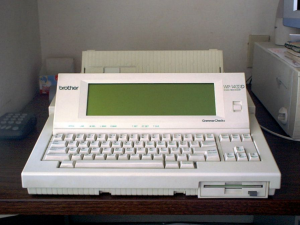

In the late 1970s, before the advent of the home computer, I lusted after the fancy-dancy, daisy-wheel electronic typewriters. The LCD or CRT displays on those babies, like the Brother WP models, allowed you to see and correct mistakes before the page printed. They boasted built-in ROM editors, spell-checkers, grammar-checkers, a few kilobytes of internal RAM, plus optional cartridge, magnetic card, or diskette external memory devices for storing text, or even document formats.

Computers are the direct descendants of counters, abaci, and adding machines. Word processors were born to serve writers. The word processor’s association with computers was initially a marriage of convenience. Now the two are inseparable.

Writing on a word processor is a lot like typing. Still got the click-clack thing happening. Though the words are composed of pixels and exist only virtually, watching them grow letter-by-letter left-to-right across a “page,” mirrors exactly the visual experience of typing. Where typing and word processing differ is in the corrections. Praise be the holy backspace key.

Take that sentence above, for example, the one that begins, “Though the words are composed…” Originally it read, The visual experience of watching words grow letter by letter, moving from left to right across the screen is the same, even though… At that point my internal editor said, “Yuck, no. Clumsy.” So I went back, moved the top of the sentence to the end, trimmed, added, basically juggled words around until my internal editor was ok with it. Just took a minute to improve the sentence flow and clarity. When re-writing is this easy, there’s no excuse. You’ve got to go back, before you go on.

Back-tracking isn’t a conscious decision, for me, anyway. It’s automatic. Instinctive. I’m writing fast, here. I’m in pulp-mode, just getting it down, whizzing through it. I’m determined to get this post up by midnight, got a personal deadline to meet. Editing as I go, that’s not slowing down. That’s just how I write.

A fellow writer once said (I’m paraphrasing here), word processors make it possible for our writing to be perfect. I think it’s more than that. I think word processors compel us toward perfection. When words can be cut, pasted, deleted, restored, checked, corrected, and revised quick as thought, how can we – and why should we – resist the impulse to get them absolutely and entirely right?

Before reading your most recent series of blogs, I never thought about what could have come between the typewriter and computer. Really interesting!!

Thanks, Bryn! When I was stage managing in LA, one of my friends — a writer who made her living as a light-board operator — got a brand-new Brother. I was simply agog at its capabilities, especially the correct-before-you-print function and the memory. I drooled over it for maybe a year, then thanked my lucky stars I hadn’t bought one. The hey-day of the electronic typewriter was super short. Guess they’re still a thing. Brothers and IBM daisy-wheels are still being sold for $100-$250 at Amazon, Office Depot, and the like. Once word processors hooked up with affordable personal computers, though, why would anyone want anything less?